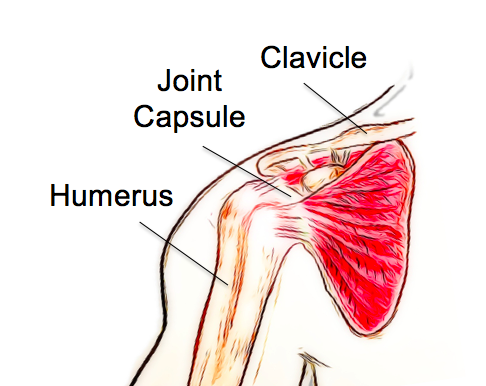

Frozen shoulder, also known as adhesive capsulitis, is a condition affecting the joint capsule of the shoulder. It is characterized by inflammation of the capsule, leading to pain and stiffness with shoulder movements.

Frozen shoulder is categorized as either primary or secondary. Primary frozen shoulder occurs for no clear reason, while secondary frozen shoulder develops following an injury or surgery of the joint.

Frozen shoulder usually follows a typical pattern and can be separated into three stages, freezing, frozen and thawing. The pain begins in the freezing stage as an ache or twinge with movements. The pain gradually increases, and the shoulder begins to feel stiff as well as painful. Usually, shoulder movements away from the body or rotating outwards are the most painful and restricted.

As the condition progresses, everyday activities can be significantly impacted, with activities such as dressing, grooming, reaching overhead and behind the back becoming difficult. Lifting heavy objects can be very painful, and the pain is often felt at night-time, interrupting sleep. The three stages follow a typical pattern;

Freezing – Pain is present at rest/night, increasing pain and stiffness with shoulder abduction and external rotation.

Frozen– Pain starts to lessen, but the stiffness of the shoulder joint increases.

Thawing – Pain reduces to lower levels and movement begins to return.

Frozen shoulder will usually resolve on its own without any long-lasting stiffness. However, complete recovery does not always occur.

Frozen shoulder usually affects people over the age of 40 and women are affected more often than men. While no definite cause has been identified, there are some factors that increase the risk of developing a frozen shoulder. These include diabetes, prolonged immobilization, trauma, stroke, thyroid dysfunction, heart disease and autoimmune disease.

The early stages of frozen shoulder can mimic other shoulder conditions, and these should first be ruled out by a thorough examination. While frozen shoulder is a self-limiting condition, meaning it will resolve on its own without treatment, this can take up to 2-3 years. Physiotherapy during this time focuses on reducing pain as much as possible and helping patients to cope and adapt to their symptoms during the freezing and frozen stages.

As the condition moves into the thawing stage, physiotherapy aims to help restore strength, movement and control to the shoulder. The entire process can be extremely distressing for patients and providing support and education as they move through the stages of the condition is an essential part of treatment.

If you have any concerns about shoulder pain that is not resolving, come and have a chat with one of our physiotherapists to see how we might be able to help you. None of the information in this article is a replacement for proper medical advice. Always see a medical professional for advice on your injury.